The Partner Bank Boom Revisited

/Amber Buker is the chief research officer for the Travillian Group, a national executive search and advisory boutique. She consults with banks on technology partnerships, product development, and business development in Indian Country.

It’s a little untoward in journalism to acknowledge the writer. But to tell this story, we’re going to break the fourth wall because I had an up close and personal look at what leading Silicon Valley VC firm, Andreessen Horowitz (A16Z), once dubbed “The Partner Bank Boom.” And it was a wild ride.

In 2020, I was working with a group of innovative banks that gave me a catbird seat to witness the Covid-induced digital-banking proliferation that led to the Partner Bank Boom. Learning from those bank leaders gave me some of the critical insights I needed to build my own venture-backed fintech. In 2022, I became the second Indigenous woman in the US to raise a multi-million dollar venture round to build Totem — the only digital banking and payments platform for Tribes and their People.

We worked shoulder-to-shoulder with our sponsor bank to develop policies, procedures, and a novel flow of funds to serve our tribal customers. We chose a bank that would partner with us directly, so that we didn’t have to count on intermediaries (“middleware”) keeping everything straight. At the time, some banks already had serious reservations about the role those companies were playing. But other banks were asleep at the wheel. Shockingly, more than one “No KYC” account was allowed to launch around this time.

But nothing could have prepared me for how big the blast radius would be when the partner bank boom went bust. The implosion of Synapse — one of the first middleware providers and an A16Z portfolio company — sent the industry scrambling. It mobilized regulators into executing a massive crackdown on the banking-as-a-service (BaaS) model. And it resulted in a wave of consent orders, the repercussions of which are now showing up in banks’ financial performance.

My startup was a casualty of the crackdown. Our partner bank exited the space citing extremely high regulatory thresholds and related expenses, and they weren’t alone. Around the same time, Five Star Bank ($6B, NY) and Metropolitan Commercial Bank ($7.2B, NY) did the same. More banks just quietly stopped accepting new programs, while others dramatically raised their requirements. We’ll never know how many banks never went through with plans to enter the space.

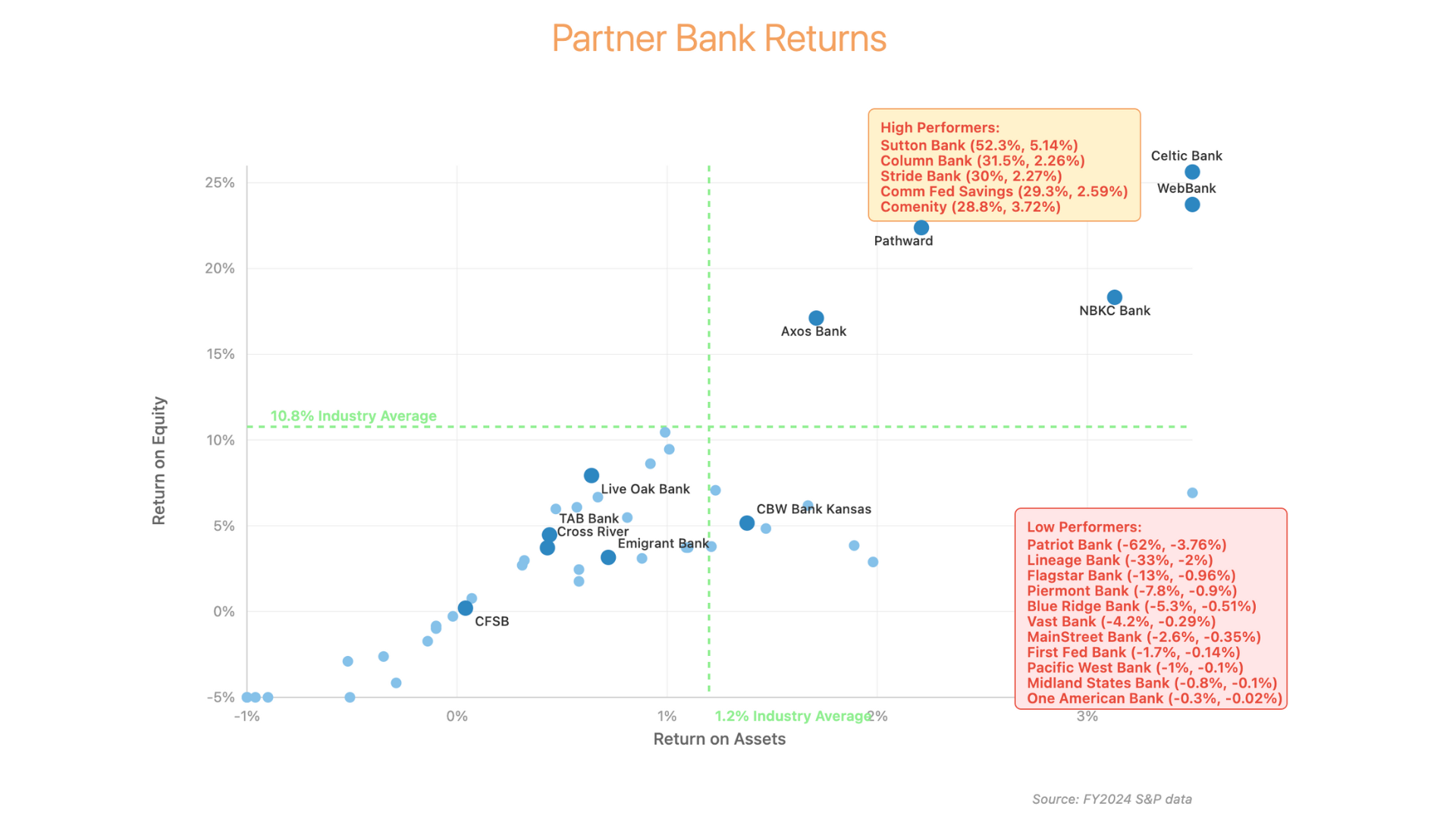

While the BaaS model is not dead, a look at the financial performance of sponsor banks at the end of 2024 paints a sobering picture. In the image that emerges, a wide gap now separates the sponsor bank haves and have-nots.

The Math’s Not Mathing

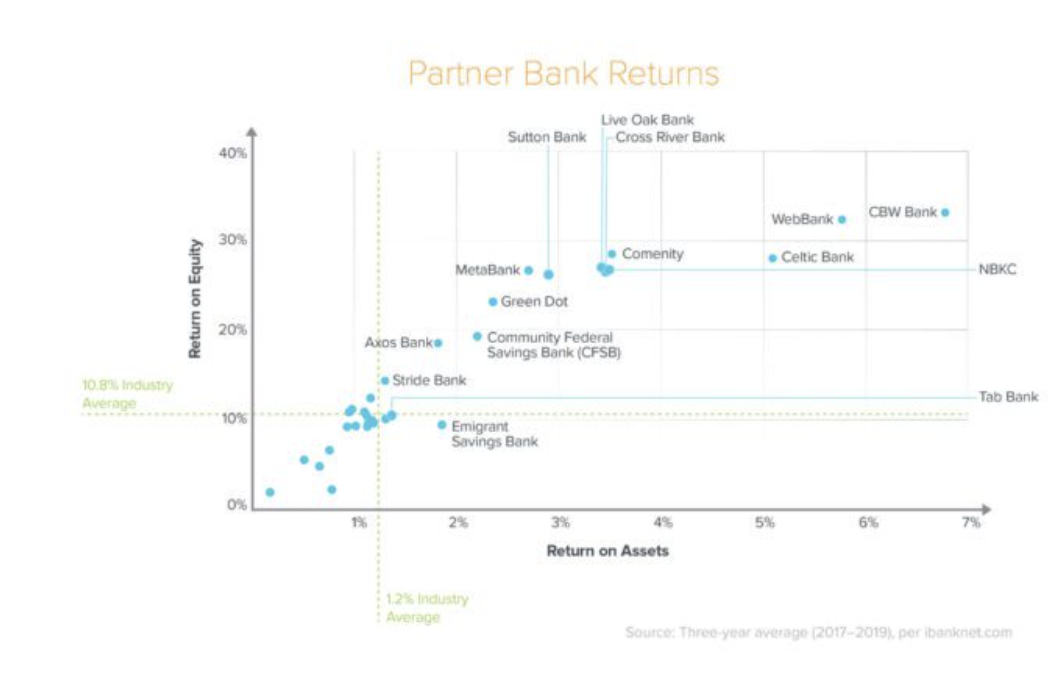

The much-shared chart from A16Z’s original Partner Bank Boom article first appeared in 2020. It features an early cohort of 30 banks who were offering BaaS at the time. But the view has changed quite a bit in the interceding years as the performance ratios for all but two of the featured institutions slid down and to the left.

Original A16Z Chart, 2020

Updated Travillian Chart, FY2024

In an analysis of 67 banks that are under $10B in assets and offer DDA account/debit card programs, Travillian found that the average return on assets (ROAA) was just 0.80%, which is well below the 1.0-1.2% that’s typical for healthy community banks. More than 1 in 6 sponsor banks posted negative returns.

To understand why these performance numbers are so surprising, you have to grasp how the BaaS model was supposed to revolutionize bank economics. Unlike traditional banking, where institutions generate 3-4% net interest margins on loans, BaaS banks earn interchange revenue on deposits — creating income without traditional credit assets.

The top performers demonstrate the model’s potential. Sutton Bank’s 52.3% ROAE demonstrates exceptional profitability relative to their equity base; they’re generating returns that are roughly 4-5 times higher than typical community bank performance. That’s a feat that is only possible through massive interchange volume relative to their asset base.

When properly executed, BaaS creates revenue density that traditional banking simply cannot match: interchange income flows from deposit balances that require minimal regulatory capital, no credit underwriting, and no loss provisions.

When the Model Breaks Down

Yet the majority of BaaS banks are failing to capture these economics. The performance spread reveals which institutions have successfully built interchange-driven revenue engines versus those carrying traditional banking cost structures without the volume to justify them.

Low performers likely suffer from several factors. Some banks maintain conservative capital ratios despite the lower risk profile of interchange revenue, limiting their return on equity potential.

Technology and operational inefficiency can consume interchange margins through high processing costs.

But among the factors within the bank’s control, picking the right partners seems to be a skill that separates top performers from the rest. Banks that have been in the business for longer (and who have already survived their own consent orders) like The Bancorp ($7.9B, DE) and MetaBank (now Pathward) have their pick of the most-hyped, best-funded startups. Their client rosters include brands like recently-IPOed Chime and MoneyLion, which boasts 20 million customers, respectively.

With 65+ BaaS banks in the space, newer entrants generally compete downmarket for fintech partners with less brand recognition and a whole lot less funding. This creates concentration risk for banks that have too few partners who are more likely to fail than not.

For those organizations, compliance overhead without the scale to support it leads to heavy regulatory costs being divided across insufficient interchange volume. That math just doesn’t math.

The Regulatory Reckoning

Another factor that divides the haves and have-nots is whether the institution is under an active consent order. According to S&P, banks with enforcement actions averaged just 0.25% ROAA compared to 0.92% for their unencumbered, non-BaaS peers.

The breadth of regulatory failures that recent orders exposed is staggering, and dealing with them is expensive. For example, the order against Evolve Bank & Trust ($1.8B, TN) cited failures in board governance, consumer compliance, BSA/AML, internal audit, third-party oversight, credit risk, interest rate risk, operational risk, financial risk management, liquidity risk, and business restrictions. These aren’t isolated compliance gaps; they represent fundamental failures in risk management that require comprehensive remediation efforts.

What makes these enforcement actions particularly devastating for BaaS banks is how they destroy the fundamental economics that make the model viable. The beauty of interchange revenue is its scalability. But enforcement actions reverse this dynamic by creating massive, fixed costs that scale with transaction volume.

When a consent order requires a BSA review of every transaction since 2022 — as the recent order aimed at Piermont Bank ($550M, NY) did — the bank is not just paying for future compliance. It’s being asked to retrospectively apply current standards to potentially millions of past transactions. This represents an enormous forensic accounting exercise that could cost millions.

Many banks will need to staff up to meet the demands of remediation, which only compounds the personnel deficiencies that likely contributed to the consent order in the first place.

Brian Love, Head of Banking & Fintech Search at Travillian Group, says his practice is seeing an uptick in banks that are seeking staffing help several levels below his usual C-suite placements. “We know banks that are paying a lot of money to consultants to take on BaaS-related work their existing teams can’t. But relying on outsourced talent is an expensive stopgap that can leave institutions ill-prepared for future growth or scrutiny.” As a result, Love notes, he’s being asked by more clients to help place entire teams, especially for BSA.

Survivors vs. Strugglers

Not every BaaS bank is underperforming. The top institutions demonstrate that profitable BaaS is possible. But these success stories share common characteristics: the bank typically got in early, invested heavily in compliance infrastructure, and maintained disciplined underwriting standards.

For example, Celtic Bank ($3.7B, UT) has been a leader in small business lending partnerships since its early relationship with Kabbage in 2008. Sutton Bank’s partnership with Marqeta dates back to 2011, giving it nearly a decade to refine its processes before the recent regulatory tightening. These aren’t overnight success stories — they’re institutions that spent years building the operational discipline that BaaS demands.

It’s also possible to find BaaS success as a newer entrant to the market. Coastal Community Bank ($4B, WA) started looking into BaaS in 2015. The business didn’t really take off until 2020, but the bank’s BaaS division, CCBX, grew so fast that it had to add additional staff by 2021. At the time, Coastal Community Bank CEO Eric Sprink told the Financial Brand that they had only onboarded a fraction of the programs they interviewed — around 2%.

Coastal’s disciplined growth has led to solid financial performance. The BaaS division brought in noninterest income of $5.6 million for the three months ended December 31, 2024, and the bank completed a $98.0 million common equity raise at the end of last year. With a price of $71.00/share — a premium relative valuation compared to bank industry medians — Coastal represents a bright spot in the BaaS landscape.

Looking Forward

Through the lens of a fintech founder, the regulatory crackdown creates existential challenges. There are less banks to work with, and the ones staying in the game have dramatically raised their standards for new programs.

In a parallel to the bank’s situation, the fintech world is also being divided into the haves and have-nots. The haves are struggling to secure back-up banks in case they get kicked off an existing program. The have-nots may never be able to raise the level of capital that sponsors now require just to get in the front door.

The original A16Z thesis wasn’t wrong — partner banks can generate superior returns when the model is executed properly. But the data shows that “properly” now requires a level of compliance infrastructure that many banks underestimated. The question now is whether the survivors can rebuild confidence in a model that promotes access and innovation in a highly regulated industry.

This piece was originally published in Travilian Next, a publication focused on banking and fintech strategy.